This post is from Doug’s blog, the Contrarian Mindset. We’re sharing it here because it forms an important part of our investment philosophy at Loup.

All investing explores a simple question: What is going to happen?

Investors attempt to allocate capital to efficient sources that generate acceptable return for the risk taken. Allocating capital is always an exercise in predicting the future — that is the risk component of any allocation. The future very likely will not be what we expect, and greater uncertainty about the future usually results in greater risk premiums.

Great investors don’t just ask what is going to happen, but what is going to happen that the rest of the market doesn’t expect? Answers to the latter question yield non-consensus ideas that, when right, offer extraordinary returns because the risk must be necessarily mispriced.

The following post presents a scoring process I’ve built to help assess the worthiness of non-consensus ideas. Since the post is a longer one, I’ll present it in two core sections and an appendix:

- Components

- Scoring

- Appendix: Examples

Components

The question of what will happen can be broken into three components to score a non-consensus idea:

- The prediction

- The timing

- The magnitude

The prediction is a binary assessment of whether you think something will happen. When we have a specific idea, the question is not what but rather, “Is this going to happen?” Yes or no. In reality, predictions exist more as percentages or odds than in binaries, but action only exists in binaries. Either you act on something or you don’t, therefore you believe in the thing enough to act or you don’t. Actions are what ultimately matter, so we deal in binaries here.

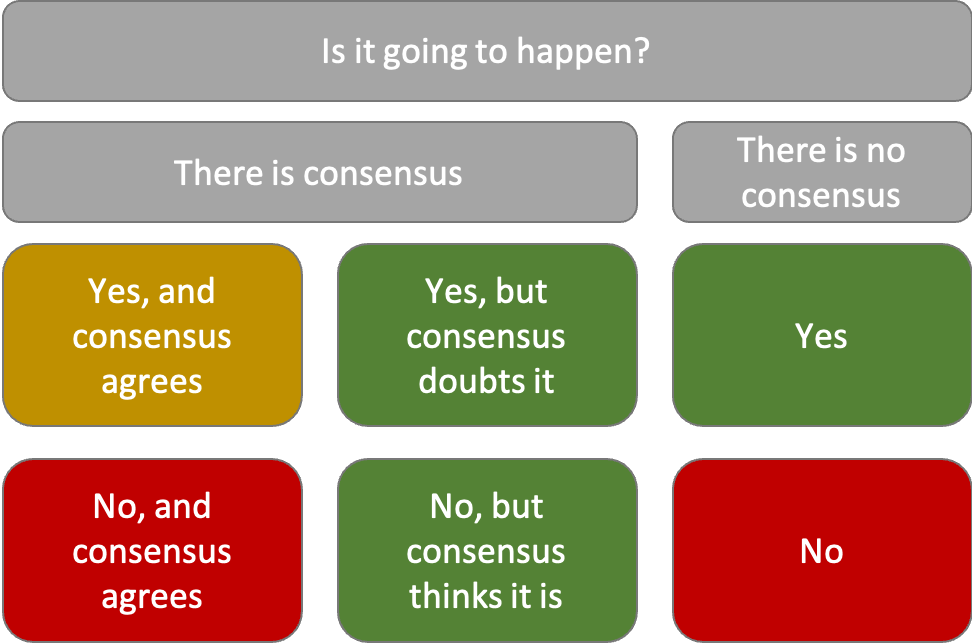

A binary prediction set offers six potential outcomes when paired with consensus:

Starting with the obvious, if you think something isn’t going to happen and either consensus agrees or has no opinion, the idea isn’t actionable, and we can remove those outcomes from our scoring tool. The remaining four outcomes — those in yellow and green — can be separated by whether the idea is priced into the market or not.

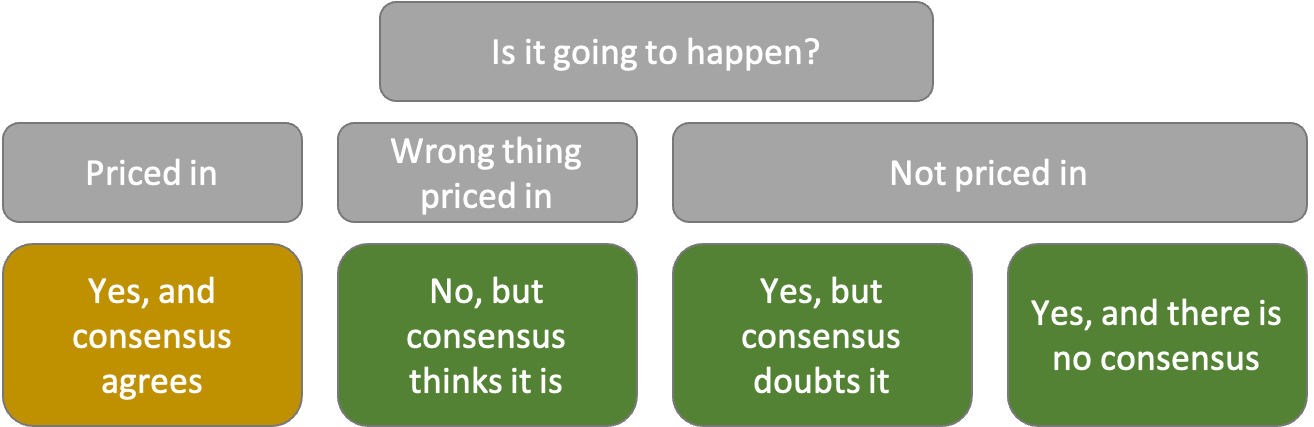

Determining what consensus expects is always a bit of a subjective exercise, but prices give us the best indicator. If consensus believes something is going to happen, whether you agree or not and whether ends up being right or not, the thing must be priced into the market to some degree. If consensus doubts something or has no opinion of it, the thing cannot be priced into the market. Relatively healthy prices should say that something is priced in, while relatively cheap prices should say something isn’t priced in. Of course, value is dependent on the eye of the beholder, so determining the beliefs of consensus is still a subjective matter that depends on the contrarian’s assessment.

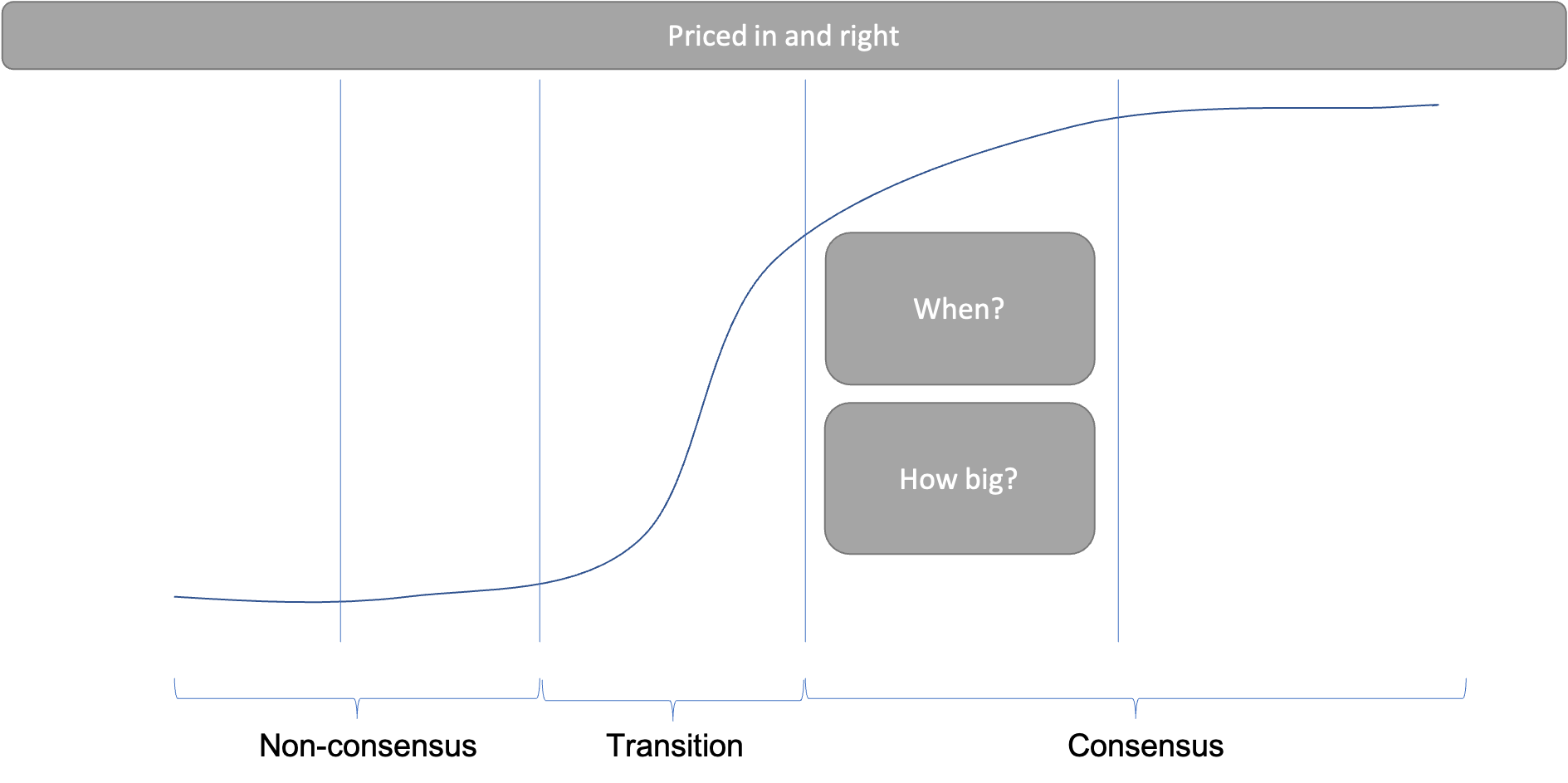

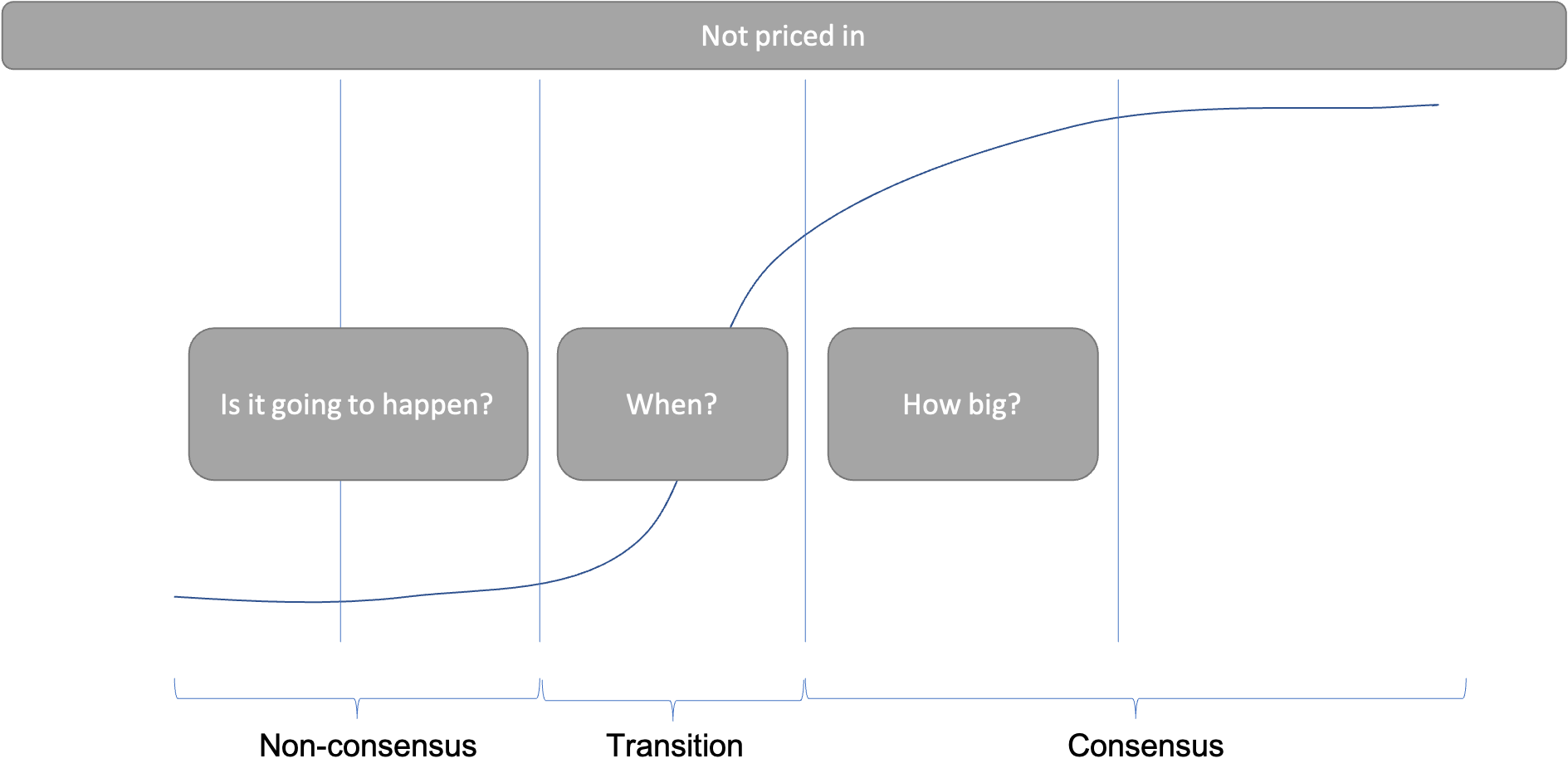

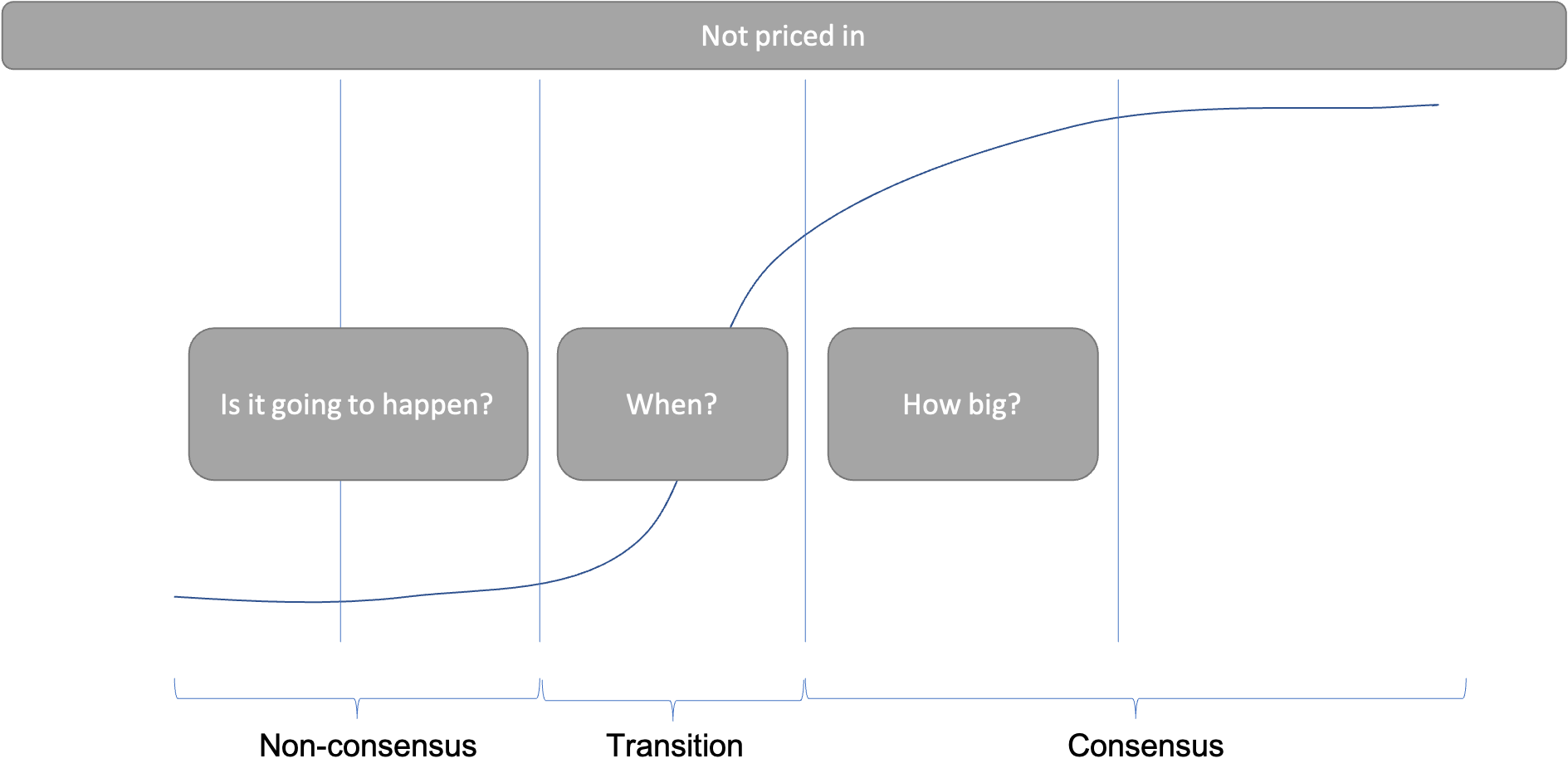

Whether or not something is priced into the market allows us to bring in the other two parameters of timing and magnitude. When something is priced in, the question of “if” is answered in the mind of consensus. It’s just a matter of time before the idea plays out and in what magnitude. We can visualize this progression on the stages of consensus chart we explored in the last post:

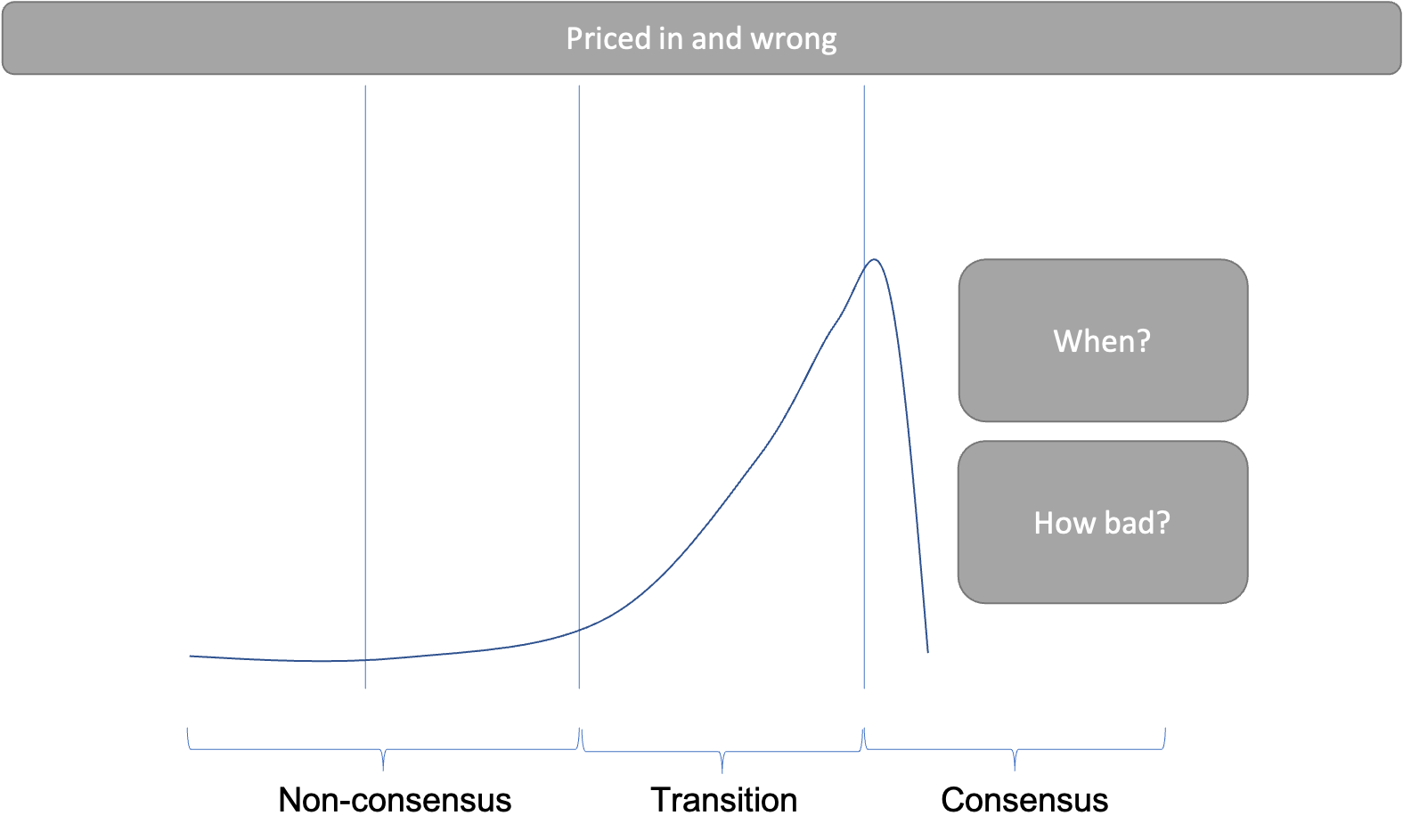

When something isn’t priced in, whether it will happen, when, and how big exist more linearly:

Timing and magnitude are closely related. Consensus in the market almost always forms some time before the thing in question actually happens since markets form to allocate resources based on future expectations. As part of the determination of timing, the magnitude of potential outcomes is also determined. The magnitude must then be discounted back to the present given the expected amount of time the thing takes to happen.

Relative to consensus, the actual timing of a thing can happen in three ways:

- Sooner than consensus thinks

- In-line with what consensus thinks

- Longer than consensus thinks

The perceived timing of something affects the steepness of the curve in the transition phase. Something assumed to happen in the relative near term necessitates a steeper curve than something assumed to happen in the distant future. This curve represents both the rapidity with which new investors will enter the market as well as how much the opportunity needs to be discounted.

Magnitude offers a similar triumvirate of outcomes relative to consensus:

- Smaller than consensus thinks

- In-line with what consensus thinks

- Larger than consensus thinks

Magnitude trumps timing assuming your investment horizon is long enough. Huge opportunities often offer very long tails where dominant companies can compound for long periods of time. Think Apple with the iPhone or Amazon with eCommerce. The longer you are able to hold on, the more leeway in getting the timing right.

Timing probably trumps magnitude if trading is the goal, although I’m not a trader. They are at least equal. The magnitude determines the payout of the trade, and good traders should look for asymmetric payouts, but if you get the timing wrong even with a huge opportunity, you could earn nothing for it if you can’t stay in the trade.

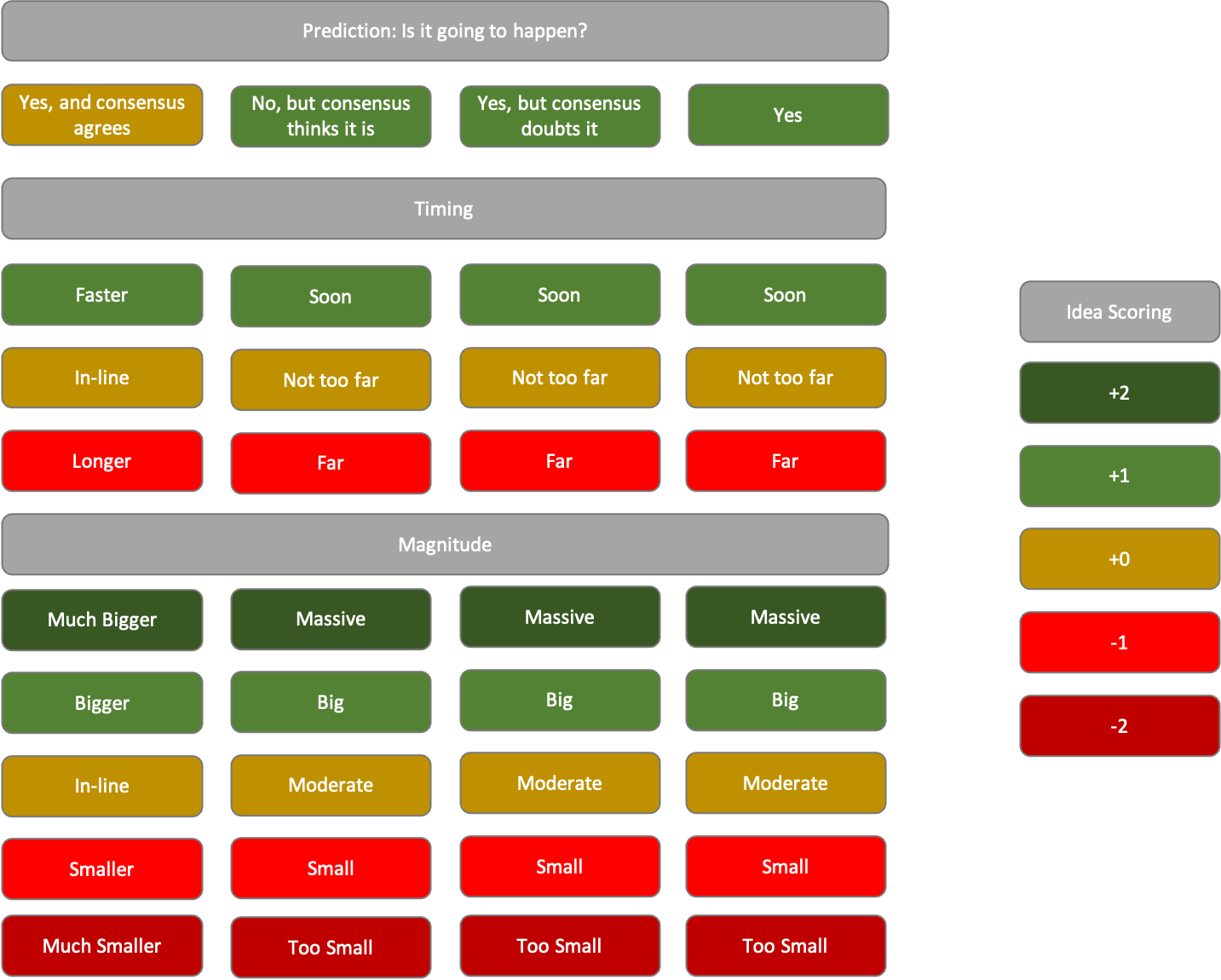

Given a prediction, timing, and magnitude, we can score potential non-consensus ideas on the Contrarian Scorecard:

Scoring

Before we can use the scorecard to assess our ideas, we need to explore why we score each category as we do. First, consider the four paths the table based on the initial prediction relative to consensus:

- You believe something will happen, and consensus agrees.

- You believe something won’t happen, but consensus thinks it will.

- You believe something will happen, but consensus thinks it won’t.

- You believe something will happen, and consensus doesn’t exist.

If you share a prediction with consensus, then consensus must misunderstand the timing or magnitude for it to be investable. If you have a view in opposition to consensus, or no consensus exists, the idea must still contain the right balance of timing and magnitude for it to be worth investing in. The scoring mechanism is designed to account for those realities.

An idea in agreement with consensus adds no points because it is already priced into the market. An idea in opposition to consensus adds one point because it precedes consensus agreement, assuming the idea turns out to be right. Recall our progression charts relative to price below. In the case of consensus pricing in an idea, the top chart, the contrarian must rely only on timing and magnitude to profit. In the case of where consensus has yet to accept an idea, the contrarian also benefits from the boost of consensus building around the idea even before it happens.

As we move to score timing and magnitude, there is an important nuance to address. Whether consensus believes something that is wrong, disbelieves something that is correct, or hasn’t contemplated the thing, there can be no valid consensus about timing or magnitude to consider. Therefore, we must consider timing and magnitude relative to consensus when it agrees with us but in an absolute sense when consensus disagrees or doesn’t exist. In other words, while timing and magnitude in path one (agreement with consensus) must be explored relative to consensus, paths two, three and four must be explored relative to the contrarian’s absolute assessment of those variables.

Timing adds or subtracts from the idea score relative to the expected speed of the event happening. Any time an idea is going to happen quickly, it should add value to the non-consensus idea because the idea is subject to less of a temporal discount. Something that will happen quickly gains one point, something that will happen at an expected or moderate pace gains no points, and something that will take a long time loses a point, especially if something takes longer than consensus thinks.

Magnitude is a more powerful variable than time, at least for the long-term investor, that should be considered across more potential scores. For magnitude, I use too small, small, moderate, big, and massive. Decent magnitude ideas add no points, small ones subtract one, and big ones add one. The extension of extreme magnitudes conveys the importance of big opportunities, as too small subtracts two points from the score, while massive adds two. Small opportunities are rarely worth exploring even if they are contrarian and going to happen quickly. Massive opportunities may be worth exploring even if they are consensus and will happen within the time expected.

As we process an idea through the above framework, we are left with a score we can judge through these criteria:

Any idea with a score less than zero is obviously bad to support, but it may be a good opportunity to short. Ideas that lose points because they are much smaller than the market expects and with near-term timing of figuring that out offer the best short opportunities.

Ideas with a score of 0 are arguably worse than those with a negative score because there probably isn’t even a good short derivative call. Zero ideas are just that. Ignore them.

Ideas with a +1 are only worth exploring in the largest of liquid markets. Think large cap equities. Probably also Treasuries. Where ideas are well scouted and assessed, even a small edge can be valuable, but don’t expect absolutely extraordinary returns.

Ideas with a +2 are what I think of as a minimum score to start getting excited. The key to assessing these ideas is understanding the tradeoffs between timing and magnitude. If the timing is soon/in-line and the market is big, the investment is safer than if the timing is far and the market is massive. There is likely additional volatility and risk (they aren’t the same thing) embedded in the extended time to the idea happening.

Ideas with a +3 are good non-consensus ideas. To score a three means that the market has a fundamentally flawed view of some idea and the timing cannot be so far as to add incremental volatility and risk as sometimes seen in +2 ideas. If you get a few +3’s right, you can have a very good investment career.

I would argue that +3 should be a minimum score to invest in something as an early-stage venture capitalist. Later stage private equity probably has too much capital to deploy relative to available investments to only do +3’s and will end up needing to explore +2’s, maybe even +1’s. Given the volume of SPACs, they’re probably lucky to get a +2, nonetheless a +1 right now.

Ideas with a +4 should only happen a few times in a career. You have to pinch yourself to make sure you aren’t dreaming because you’ll think you find more +4’s than you actually will. Is this really a +4? When you find a +4 idea, and you really believe it, you should be aggressive.

Ultimately, any non-consensus idea must be right to result in an extraordinary outcome. The initial prediction is the ultimate part of the exercise. Get it right, and you are afforded some latitude through the rest of the exercise. Get it wrong, and nothing else matters. The non-consensus scorecard can help filter ideas, but it can’t tell you whether the idea will be right or not. Only time and the markets can do that.

Appendix: Examples

To that end, great non-consensus ideas become legend. So, too, do magnificent failures. Modest failures are quickly forgotten. We can “back test” the contrarian scorecard with some memorable examples from the past that were all +3 or +4’s in retrospect. I’ll also score a few ideas from the present.

Bill Ackman’s Coronavirus Trade (+4). Ackman famously bought a credit hedge shortly before the 2020 coronavirus and subsequent shutdowns created one of the most volatile market periods in history. At the time he put on the trade, the market had no meaningful opinion on the impact of the coronavirus, i.e. no consensus (+1). The event was imminent (+1) and massive (+2).

The Big Short (+4). If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you’re probably familiar with the housing short that was one of the most successful trades in history from 2008. At that time, consensus doubted that the debt problem was as severe, I believe, because of a misunderstanding of widespread synthetic debt (+1). The meltdown was imminent in 2007/2008 (+1) and massive (+2).

The iPhone (+3). Around the time of the global financial crisis, Apple had just launched the iPhone to a fair degree of skepticism. Tech “experts” and many investors thought the phone was a niche product given it had no keyboard and relied entirely on a touchscreen. Consensus doubted the phone (+1). While adoption took a moderate time to build (+0), the market was massive (+2).

It’s worth mentioning that I almost made the prediction of “Yes it will happen, but consensus doubts it” a +2 by itself. Skepticism against an investment is a multiplier when the investment is right because skepticism reduces price and increases upward volatility as the incorrect consensus rushes to the correct side of a trade.

Inflation (-2 to +2). We’ve talked about inflation on the Contrarian Mindset before. The moves in Treasury yields say that inflation concerns are consensus (+0), but the timing and magnitude are difficult to determine, so I rank the idea in a broad range of scores. It wouldn’t surprise me if it took longer than consensus expects to see inflation, and if it were milder than expected (-2). Of course, a bear may argue that would just push the ultimate inflation-driven crash back, and maybe they’ll be right, but most trades would probably lose money waiting for that event. It also wouldn’t surprise me if inflation spiked relatively quickly and was a little more severe than expected (+2). I’m glad I’m not a fixed income trader, although the outcome of this question will obviously matter a lot for equities in the next couple of years, so it sticks with all of us.

Electric Vehicles (-1 to +1). Scoring the EV opportunity is much easier. Most likely, I think it’s a +0, at best a +1. The shift to EVs is definitely consensus (+0). If anything, the market may be thinking the shift happens too quickly (-1). Major shifts often take longer than optimistic expectations, particularly as priced by bull markets. And the auto market is relatively mature, so the magnitude of the EV opportunity is probably well understood. Maybe autonomy adds some incremental upside to the EV trade, but I find it hard to get excited about investing new money into EVs right now.

Brain Computer Interfaces (+2). Brain computer interfaces (BCIs) allow for the symbiosis of the human brain and a computer. BCIs can allow for control of computers or machines, high-bandwidth information transfer, neural disorder repair, and even brain augmentation. Elon Musk’s Neuralink ambitions have been described as a wizard hat for the brain. We’re invested in the space and are believers. Maybe it’s bias, but I think BCIs are at least a +2. There is no real consensus about them, and we think they will work (+1). It’s likely they take very long to develop (-1), but the opportunity is truly massive (+2). Maybe we’re early, and in a few years BCIs will look like a +3, but we’re pretty sure we’re going to be right if we, and our companies, can hold on.