Social media gave everyone a voice. Now we’re dealing with an unintended debate: What should those voices be allowed to say?

Amidst political conflict, misinformation, harassment, and bullying, social networks are under increasing pressure from users and governments to act on what conduct should and shouldn’t be allowed on their platforms. Last month, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg called for regulators to take a more “active role” in legislating acceptable online content.

Earlier today, Facebook decided to take action itself, banning several controversial personalities from its platforms, labeling them as “dangerous.”

The topic of free speech and social networks invites impassioned opinions from both sides that can dominate conversation. We’ve been following the free speech debate over the past several months and have been curious how the average American thinks about it, so we asked 416 American internet users for their opinions about free speech. The results show a complex mix of valuing free speech, while often being offended by what they see and displeased with how social platforms have handled content on their platforms to date.

We always think of surveys as directional rather than definitive, but the direction is clear:

- Social media companies have a content problem in the eyes of their users — more than a third of Americans find offensive or upsetting content on social media multiple times a week.

- Forced to choose one or the other, the majority of Americans value freedom of speech over doing more to limit harmful speech.

- In a Feb. 2019 speech at Harvard, Zuckerberg said, “People don’t want Facebook to be the arbiter of truth.” Our survey suggests otherwise. The public trusts tech platforms more than the government, despite what feels like frequent negative press about tech; however, more people disapprove than approve of how social media platforms are policing content today.

Here’s an overview of the data.

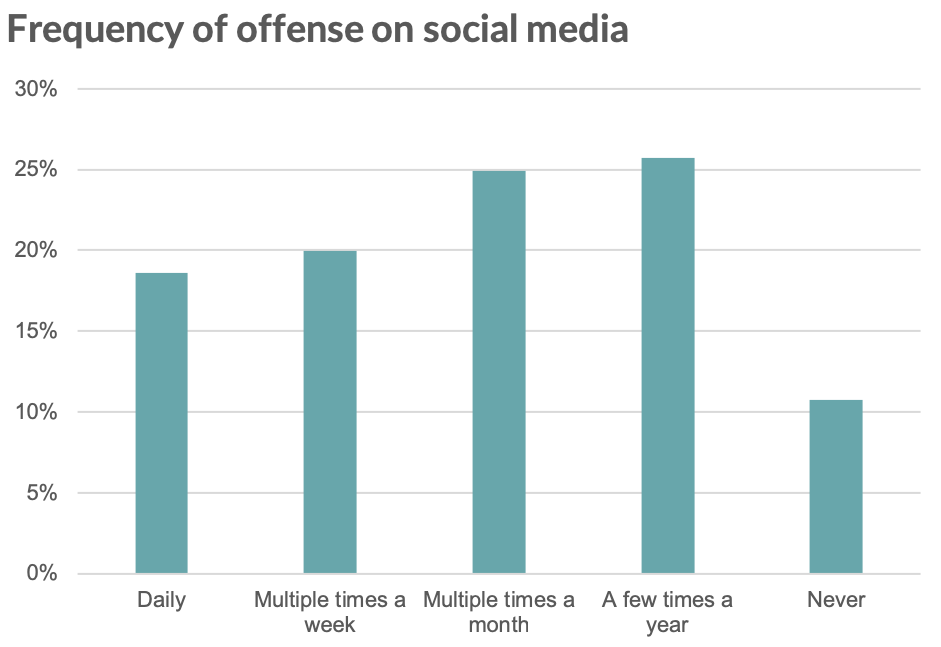

How often are you exposed to content that offends or upsets you on social media?

The toxicity of social media is real. 18.6% of respondents said they are offended or upset by something on social media daily and 19.9% said they are multiple times a week. Only 10.8% said they’re never offended or upset by anything on social media. Whether people choose to spend time with the wrong content or social media platforms push content that is more likely to engage, it’s no wonder depression is tied to social media use.

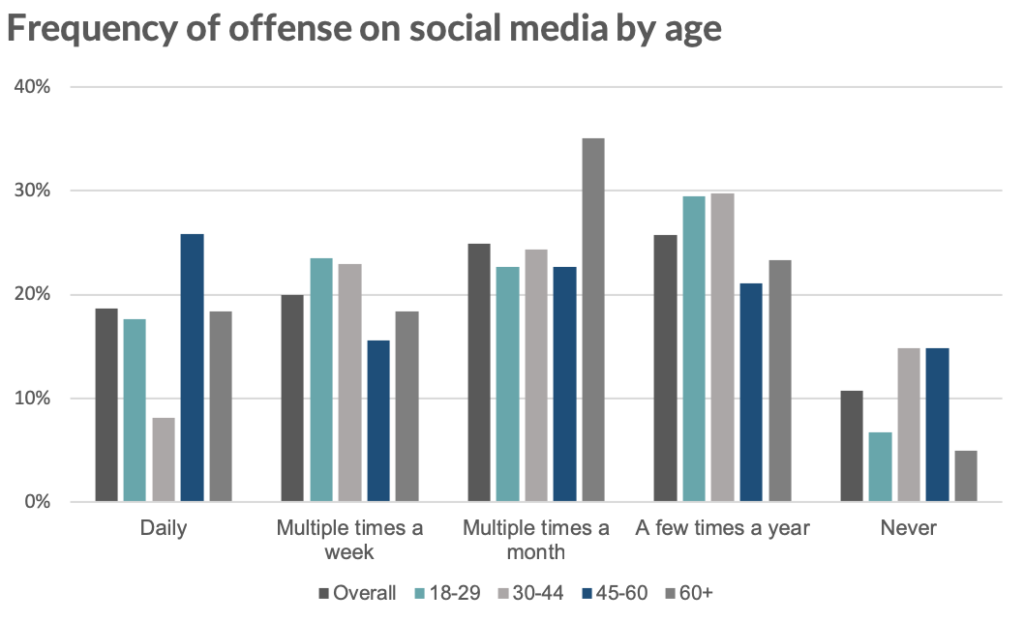

Older users find offense more often

Internet users aged 45-60 were most likely to find daily offense on social media, followed by users over 60 and users 18-29. Users 30-44 were least likely to find daily offense. The propensity of older users to find daily offense may be because older users are more sensitive to political content as bullying and harassment are likely less common for older users.

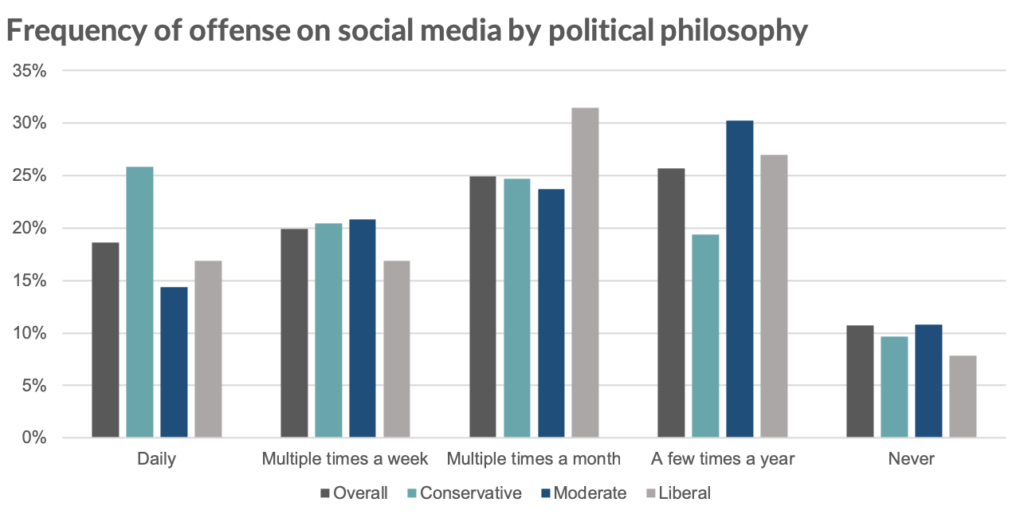

Social media offends conservatives more regularly than liberals.

Self-identified conservatives find offense more often on social media as 25.8% say they are offended or upset by social media daily compared to 16.9% of liberals and 14.4% of moderates. Perhaps unsurprisingly, moderates showed the least offense (a few times a year to never) at 41% vs conservatives at 29% and liberals at 34.8%. We’ll look at more opinions separated by political preference, but this is an early reflection of the belief that social media companies tend to have a more left-leaning bias.

Note: an equal number of respondents identified themselves as conservative (101) and liberal (100). Moderates totaled 150 users, while 65 users preferred not to answer. We note this to say that political bias was unlikely to influence overall opinions throughout the study given the equality across the spectrum.

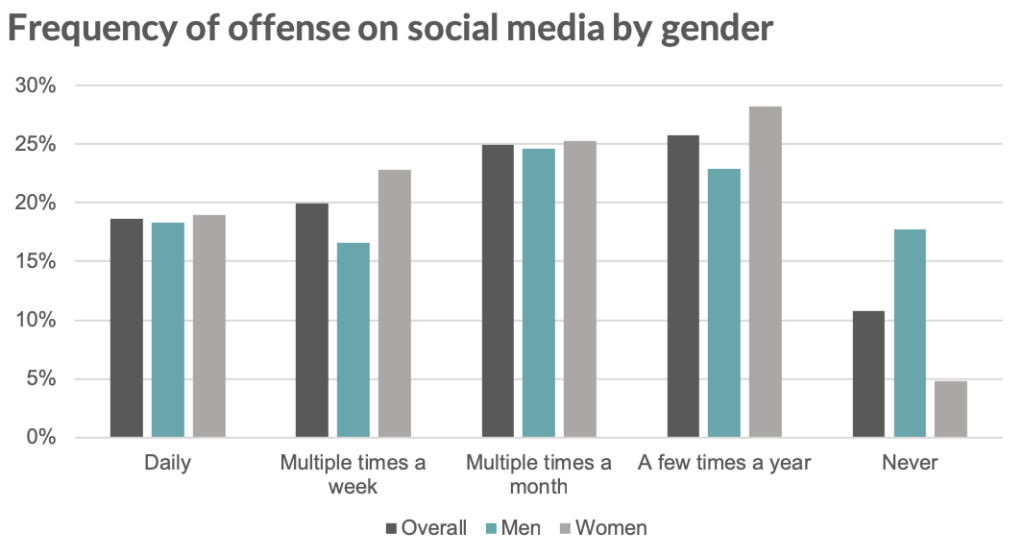

Men are less likely to be offended or upset by social media.

Men tend to be upset by social media less often than women. While both men and women are upset about equally by content on a daily basis, 22.8% of women are upset by content multiple times a week vs 16.6% of men. Further, 17.7% of men say they’re never offended by social media content vs just 4.9% of women. This may reflect that some portion of offensive content is harassment of women by men (comments on someone’s looks, unwanted romantic interest, etc.).

People who earn more are less likely to be offended or upset by social media.

We looked at the data across three income brackets: households earning less than $50k per year, $50-100k, and more than $100k. Respondents from the highest income bracket tended to be offended by social media content less often (31.5% either daily or multiple times per week) than those in either the under $50k and $50-100k brackets, which were upset by social content fairly equally (40.4% and 40% respectively).

Do social media platforms lean left or right?

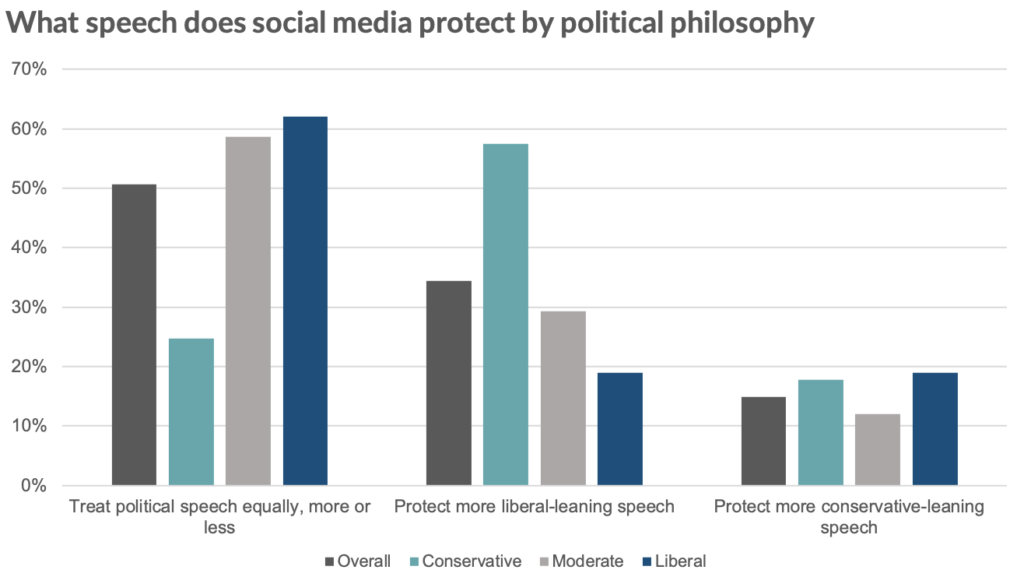

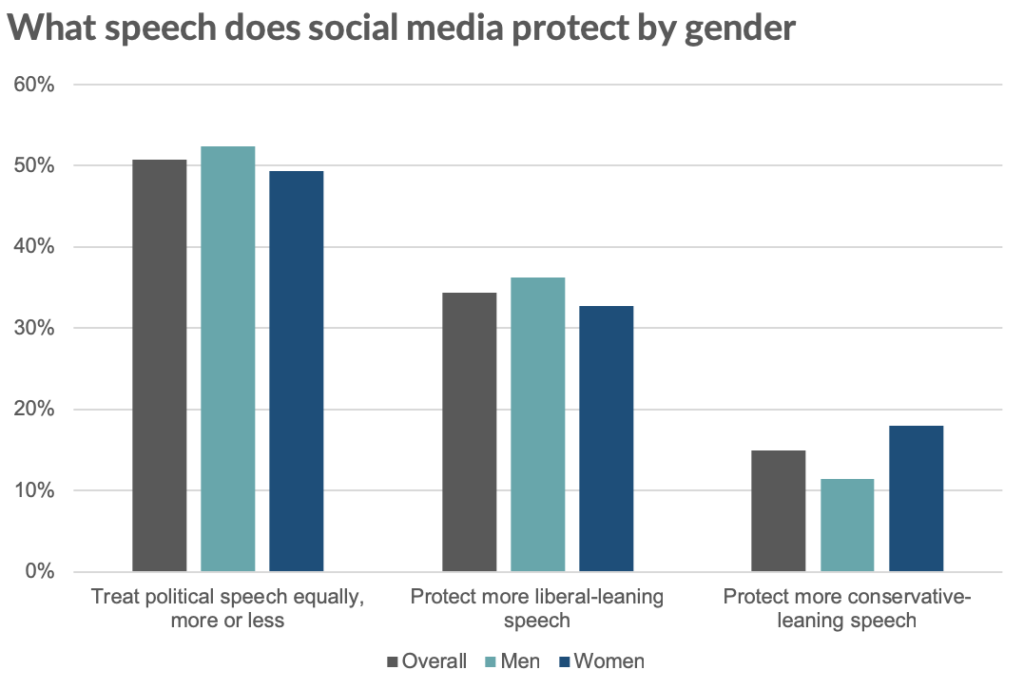

For the most part, Internet users believe social media platforms protect political speech equally (50.7%). 34.4% of respondents believed that social media platforms protect more liberal-leaning speech while 14.9% believed they protect more conservative-leaning speech.

People follow party lines, but generally believe social media protects more liberal speech

Conservatives were significantly more likely to believe that social media platforms protected more liberal-leaning speech (57.4%) than liberals were to believe that platforms protected more conservative-leaning speech (19%). Moderates, perhaps the fairest barometer, perceive more of a left-leaning bias (29.3%) than a right-leaning one (12%), although most felt the treatment was equal (58.7%).

Men more likely to see liberal speech protection, women see more conservatism

Men were slightly more likely to believe social platforms protect liberal-leaning speech (36.3%) than women (32.7%), and women were more likely to think conservative speech is more protected (17.9% vs 11.4% of men). Older respondents and higher-income respondents were also more likely to suggest a liberal bias, some of which also crossed with political philosophy.

Should we do more to protect free speech or limit harmful speech?

You cannot both protect free speech and limit harmful speech. One must give way to the other and it seems this issue is at the core of the debate about what should and shouldn’t be allowed on social media platforms. We asked Internet users which statement resonated the most:

- More should be done to protect free speech

- More should be done to limit harmful speech

- I have no opinion on free speech

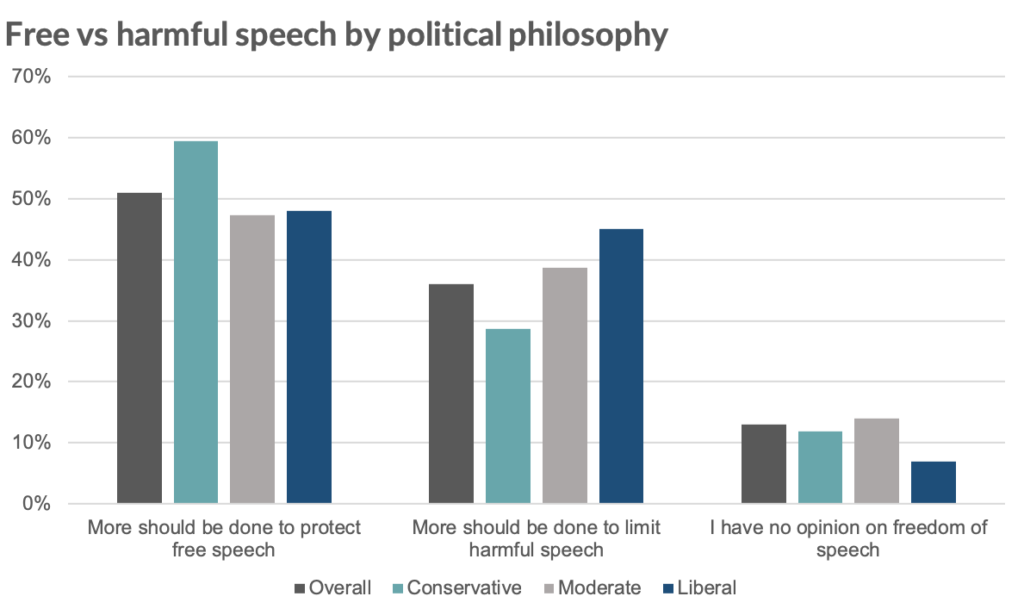

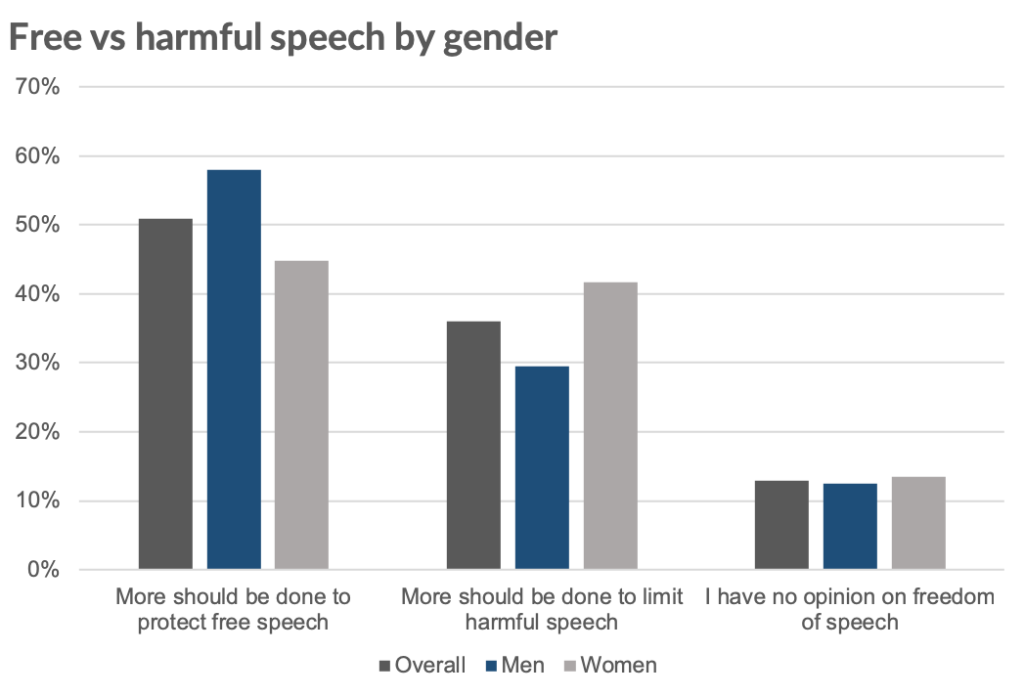

The majority of Internet users believe more should be done to protect free speech (51%), while 36.1% stated that more should be done to limit harmful speech. The remainder claimed no opinion (13%).

The lean toward more being done to protect free speech was true across political philosophy, gender, age, and income, although not always by a majority.

Conservatives, moderates, and liberals all prefer protecting free speech to limiting harmful speech

Conservatives were most likely to side with free speech (59.4%) vs doing more to limit harmful speech (28.7%). Moderates sided with free speech 47.3% to 38.7%, as did liberals at 48% vs 45%.

The difference between men and women in regard to protecting free speech vs limiting harmful speech was similar to the difference between conservatives and liberals. More than half of men (58%) sided with free speech over limiting harmful speech (29.5%), while women only slightly preferred free speech (44.8% vs 41.7%). Again, our hypothesis here is that online harassment likely affects more women than men.

Are Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social content platforms effectively policing content on their platforms?

Before we asked users if social platforms like Facebook and Twitter are doing an effective job policing content on their platforms, we asked if they should be responsible in the first place. The answer was overwhelmingly, yes. Almost 62% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that social platforms should be responsible for harmful content on their platforms, while only 14.4% disagreed or strongly disagreed. The opinion was consistent across political philosophy, gender, age, and income.

Whether those platforms are doing a good job was a different matter.

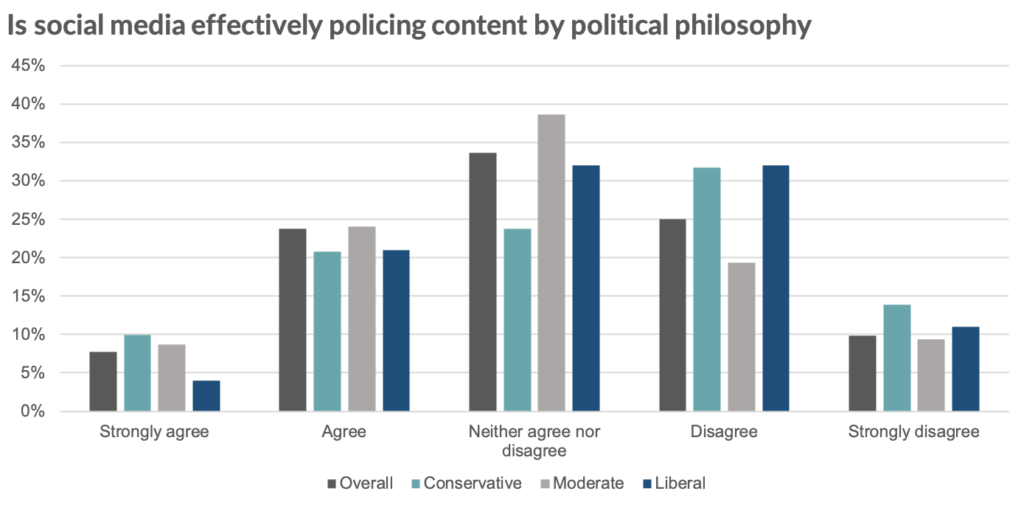

Only 31.5% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that social platforms are effectively policing content. Almost 35% said they disagree or strongly disagreed.

Conservatives and liberals actually agreed, with 45.5% and 43% saying that social platforms aren’t doing a good job policing content. Moderates were more moderate at only 28.5% dissatisfied. More conservatives thought that social platforms were doing enough to police content as compared to liberals (30.7% vs 25%). We were surprised about this at first given the assumed liberal-bias of social media platforms, but it may make sense given the conservative lean toward free speech and not wanting to see more oversight.

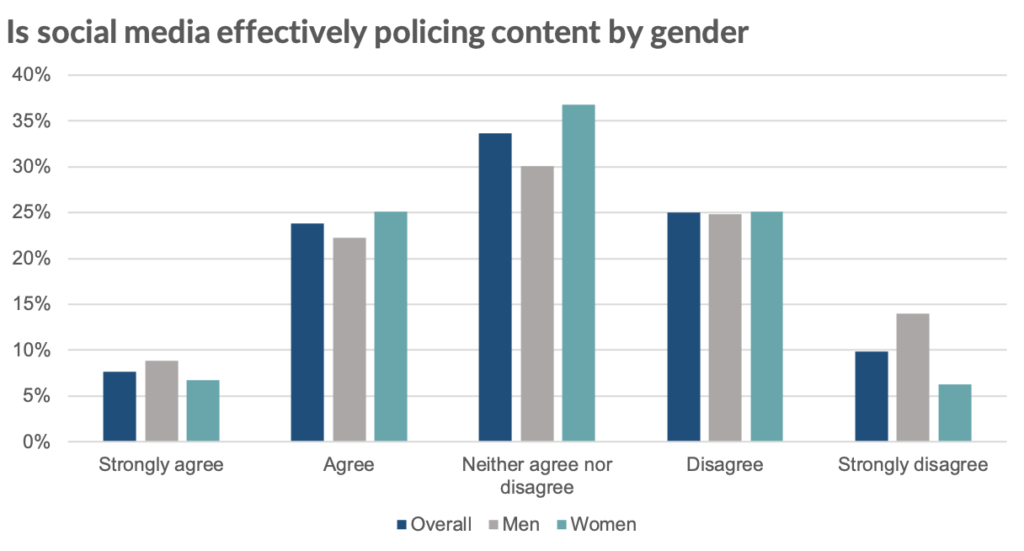

Surprisingly, men were more likely to disagree that social platforms are effectively policing content than women (38.9% vs 31.3%). We would have assumed the opposite given the data from the prior question given men meaningfully leaning toward more free speech and women feeling that more should be done to limit harmful content. This may be partially explained by fewer men offering a neutral response than women, which we discuss later.

Who would you prefer to be in charge of deciding acceptable speech?

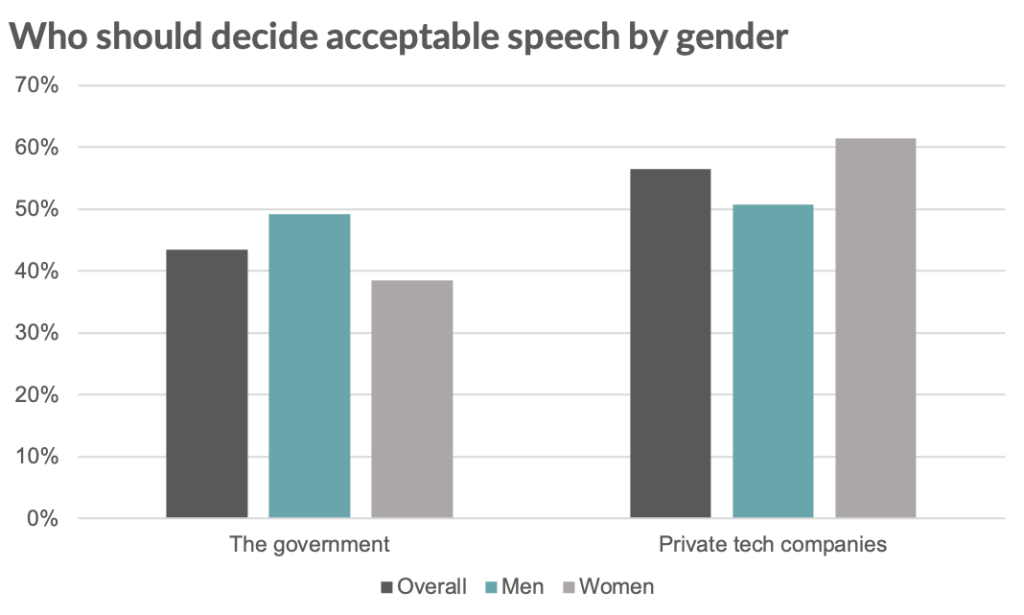

Our questioning culminated in asking who Internet users would prefer to decide what is and isn’t acceptable speech: the government or tech companies? In somewhat of a surprise given the negative media environment around big tech companies and the frequent privacy scandals, the majority of respondents said they would prefer tech companies to decide what is and isn’t acceptable speech. Media perceptions are not always an accurate reflection of public perceptions.

There was little variance of this opinion by political philosophy, although women showed a greater trust in tech companies than men — 61% of women preferred acceptable speech be determined by tech companies vs 51% of men.

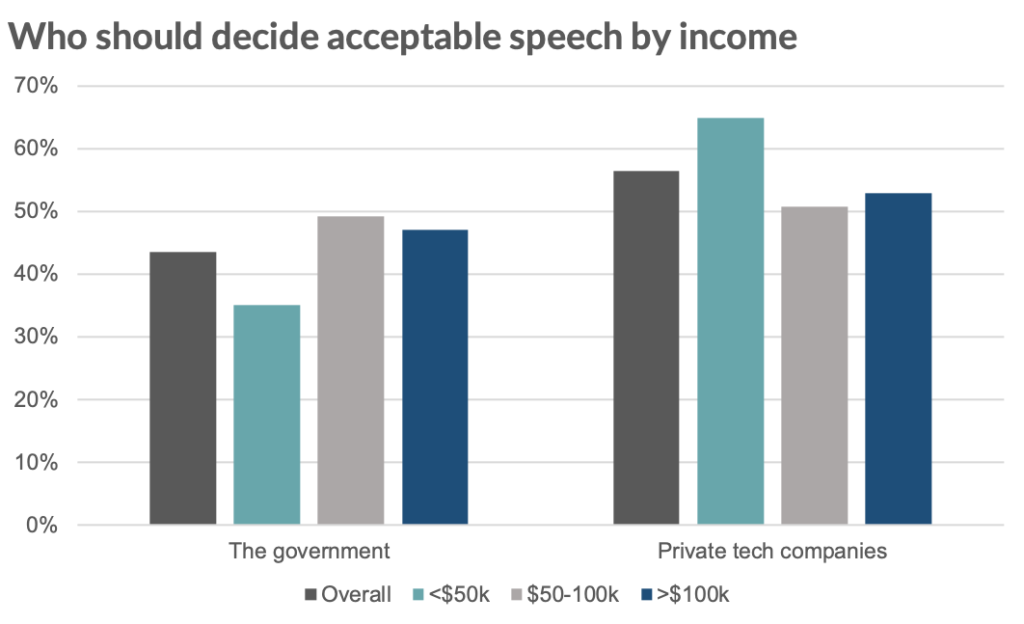

Income also showed a significant difference in preference between the government and tech companies. Almost 65% of lower-income respondents preferred tech companies vs the government while middle and higher-income respondents were closer to even (51% and 53% in favor of tech, respectively). This is perhaps a result of the perception that the government doesn’t take care of lower-income citizens, thus there is a general lack of trust.

Other observations

There were two things we weren’t looking for but struck us as we looked at the data: women and lower-income earners were noticeably more likely to offer a neutral or non-opinion than men or higher-income earners. We classify a neutral or non-opinion answer as “neither agree nor disagree” or “I have no opinion on free speech.”

The number of female respondents was about 15% greater than male. Even after adjusting for that difference, women gave 45% more neutral or non-opinion answers than men.

The difference between lower and higher-income respondents was even greater. There are 98% more lower-income respondents (<$50k household income per year) than higher-income respondents (>$100k per year). Adjusting for this difference, there were 60% more lower-income respondents that offered neutral or non-opinions than higher-income users.

We’re not sociologists, but it the data seems to indicate that there is more to be done to empower certain groups to make them more comfortable in offering their opinion or perhaps even forming an opinion.

What should social media companies do?

Social media platforms are in a difficult position. Even after the action taken by Facebook today, there will be many who believe the company hasn’t done enough to limit hateful speech and many who believe that Facebook has already done too much, even if they don’t support the opinions of those who have been banned.

Our survey suggests that the public wants social media platforms to do a better job moderating content on their platforms but maintaining free speech while limiting harmful content may be a near impossible task. There are examples of obvious hate speech and harassment that most rational people would want eliminated from social media platforms; however, once we step outside the obvious, determination becomes much harder. It invites questions of intent vs perception, science vs religion, and one person’s morality vs another’s.

Granting the power to determine acceptable speech to social media platforms alone, even though the public has more trust in tech companies than the government, feels like a difficult bargain. It would grant significant power to a small group subject to their own biases and viewpoints that may not reflect those of America. Even an independent and impartial board would be hard pressed to serve the diverse views of hundreds of millions of Americans.

Perhaps the problem isn’t solvable. Perhaps where we stand today, with ideologies from all sides sharing a mutual discomfort, is the best we can do if we want to preserve free speech. Perhaps we need to accept the trade-offs that come with any granted freedom. Perhaps the only thing we can be sure of is that the discussion is far from over.

Disclaimer: We actively write about the themes in which we invest or may invest: virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and robotics. From time to time, we may write about companies that are in our portfolio. As managers of the portfolio, we may earn carried interest, management fees or other compensation from such portfolio. Content on this site including opinions on specific themes in technology, market estimates, and estimates and commentary regarding publicly traded or private companies is not intended for use in making any investment decisions and provided solely for informational purposes. We hold no obligation to update any of our projections and the content on this site should not be relied upon. We express no warranties about any estimates or opinions we make.